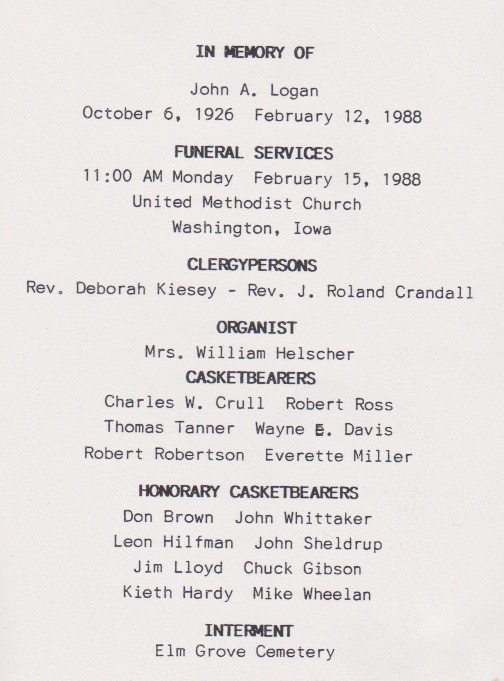

Month: January 2017

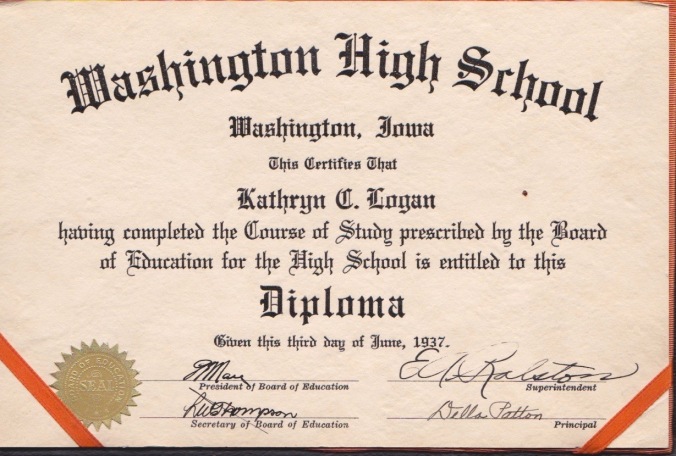

Diploma: Kathryn C. Logan, Washington High School, Washington, Iowa, 1937

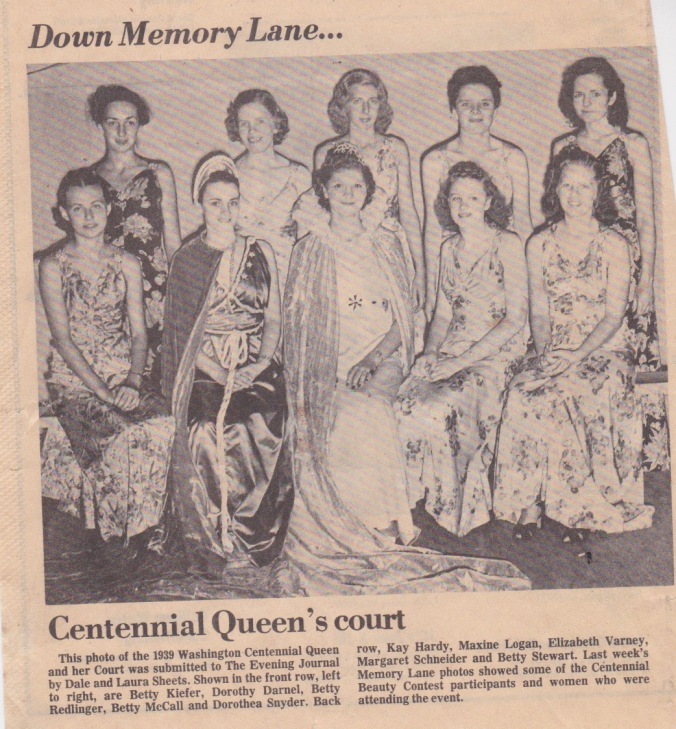

Maxine Logan, Washington, Iowa, Centennial, 1939

Maxine Logan was the daughter of Al Logan and DeIna Buhrman Logan. This photograph from the Washington Evening Journal, Washington, Washington County, Iowa, was shared by Jim Logan.

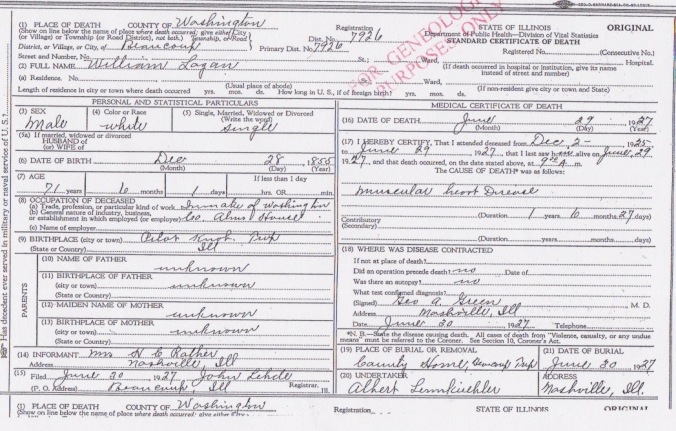

Death certificate, William J. “Bay” Logan, Washington County, Illinois, 1927

This is thought to be the death certificate of William John “Bay” Logan, son of William Logan and Matilda Thaxton or Thackston Logan.

There are some uncertainties. Although we know — from Naomi Logan Bass, daughter of William Logan’s brother, Enoch F. Logan — that “Uncle Bay” … came to our house before my dad died and stayed a while. He was almost blind. Since Enoch Logan died in March of 1924, it could help explain why Naomi lost track of “Uncle Bay” until his death in 1927. Another uncertainty is that we can’t seem to find William J. Logan in a couple of censuses. He had been living in Cherokee County, Kansas, but his mother died there in 1897 and his father in 1905 at the Cherokee County Farm. We lose him for a time afterward.

Since William Logan was “almost blind” and had “muscular heart disease” for a year-and-a-half, it makes sense that he would have lived at the County Farm, the only “safety net” other than family prior to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s and 1940s.

William Logan died in 1927 and is buried at the Washington County Poor Farm Cemetery in Beaucoup Township, Washington County, Illinois. A large stone marker adjacent to a farmer’s field lists the occupants of the cemetery, including William; however, there are no individual markers and nothing to mark even the cemetery’s boundary.

(William J. Logan was called “Bay.” His brother, Drury Logan, was called “Boy.”)

More Twins!

One of the remarkable features of our extended Logan families is the number of twins we find. An entire section in the addendum of Logan Connections details our known twins — and that list continues to grow. It appears we’ve found another set, assuming that the Ryal / Rial / Riley Logan family, descended from Esom Logan, is, in fact, “our” Esom Logan. That is assumed, but not yet proven, to the best of my knowledge.

The twins are William and Allein Logan, born 7 July 1882, children of Ryal Thomas Logan / Thomas Riley Logan and Jennie Cele Wood Logan. This research was done by Barbara W. Austin and found in her Family Group Sheet, detailed in the Logan Newsletter of January 2001, Vol. 5, No. 1.

If any of our readers have more information on twins we might have missed in Logan Connections, we’d love to have it. Thank you.

More information on Larkin Chew of Spotsylvania County, Virginia (part 2)

Two articles, “The Silver Mine in 1713,” in Beyond Germanna, Vol. 12, No. 5, September 2000 by Stephen Jacobsen and John Blankenbaker and “The Silver Mine Patent” by John Blankenbaker have additional information on Larkin Chew. Some excerpts:

“In 1713, Larkin Chew patented 4020 acres that lay on both sides of Mine Run in present day Orange County, Virginia.” Fractional interests were quickly sold and Chew himself was left with only a fractional interest. (One of those to whom an interest was sold was Alexander Spotswood.) The sales were in Essex County, Virginia, one of the parent counties of Spotsylvania County.

Apparently, this mine was not successful.

The above might lead us to see if early Essex County, Virginia, records have anything to offer us on William Logan. Might he have been associated with Larkin Chew at this early date either as an indentured servant or workman?

Also, it’s interesting to note that Essex County was created out of old Rappahannock County. Rappahannock County is where we find one of our earliest potential — unproven — Logan connections: Margaret Logan. This is pure speculation at this point, but is intriguing for further study.

More information on Larkin Chew of Spotsylvania County, Virginia (part 1)

William Logan is referenced several times in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, court documents in conjunction with Larkin Chew. We have assumed that either William Logan was an indentured servant of Larkin Chew, or a former indentured servant of Chew’s, or perhaps he simply worked for Chew. We know they lived in close proximity from the interactions cited in court documents.

The excerpts which follow concerning Larkin Chew give us a bit more to go on in terms of Chew’s possible relationship with William Logan. More pieces of the puzzle. The source is “Larkin Chew of Spotsylvania County and His Family” by Rudolf Loeser, The Virginia Genealogist, Vol. 47, No. 1, January-March 2003 and Vol. 47, No. 2, April-June, 2003. The editor of The Virginia Genealogist is John Frederick Dorman.

“Larkin Chew deeply offended Alexander Spotswood [for whom Spotsylvania County is named], who damned Chew as that “base, drunken, infamous … vilest of fellows.” Chew had served me as a Common Carpenter for Wages….” [In other words, originally Chew was not a “gentleman” by birth or status in Virginia; that is, he “worked with his hands” for “wages.” Later, as we’ll see, Chew did achieve gentleman status.]

Larkin Chew’s age: “Spotswood was 48 years old in 1724 while Larkin Chew was about five years older.”

“Larkin Chew is thought to have come to Virginia from Maryland. His father is supposed to have been Joseph Chew of Virginia and Maryland, son of the immigrant John Chew of Jamestown.” [Unproven, as far as I know.]

Chew “married into the family of Roy.” [William Logan is referenced in Spotsylvania County documents in conjunction with John Roy as well.]

Larkin Chew was a carpenter and surveyor. Again, because he “worked with his hands,” he would not initially have been a member of the gentleman class in Virginia at that time. Class was highly important in the colony of Virginia at that time. Chew’s skills led to wealth which led to county offices which led, in turn, to gentleman status.

Chew was a member of the Essex County, Virginia, militia. Essex County was one of the counties from which Spotsylvania County was created. John Roy was an Essex County planter.

In 1722, “Larkin Chew and his son Thomas were sworn justices of the peace. Appointment to this office entitled Larkin Chew by common usage, to style himself ‘Gentleman.'”

In 1723 and 1726, Larkin Chew was a Burgess; in 1724, 1726, and 1727, one of the county coroners; and in 1728, he was appointed sheriff of Spotsylvania County. “… With his son Thomas he was vestryman of St. George’s parish….” [This is helpful because it gives us a location for Chew and, because he and William Logan lived in close proximity, it means Logan lived either in or near St. George’s Parish. (We have a reference from 1734 where William Logan is a witness to a document concerning land sold for a glebe for St. Mary’s Parish in Spotsylvania County, so the St. George’s Parish information gives us another clue for where to search.)]

“Larkin Chew died between 7 February 1728/9 and 11 March 1728/9.” [His will is quoted in the article.] Interestingly, in 1730 and 1731, after Larkin’s death, William Logan and John Chew, Gent.[leman] were in Spotsylvania County court because of assault and battery and trespass charges. John Chew was Larkin Chew’s son. (The other children were Thomas, Larkin, and Ann.)

Some Byars information, Warren County, Tennessee

One of the intriguing places where Byars families — a name closely allied with our Logans — is found is Warren County, Tennessee. We also find numerous Cantrells there. Some of the Cantrell family were affiliated with pioneer Baptist preacher John Hightower in South Carolina, then Hightower and several Cantrells moved to Warren and Logan County, Kentucky, where Hightower worked with Baptist ministers Joseph Logan and Alexander Devin. Later still, some of these SC-KY Cantrells moved to Warren County, Tennessee.

There was a branch of the Dodsons in Warren County, TN, too. The Charles Dodson family, which moved to Warren County, Kentucky (part of which later became Allen County) from South Carolina, as did the Logans. The Dodsons and Logans intermarried in south-central Kentucky and were co-religionists as well as neighbors and friends.

As you can see, I haven’t been able to sort out all these Warren County, Tennessee, threads yet. Is there something to all this or was Warren County, Tennessee, simply an attractive pass-through area and these are coincidental occurrences?

In searching for information, I found the following tidbit in The Dodson Family of Warren County, Tennessee and Allied Families by Catherine Gaffin Lynn. If any of you have done some Logan or Byas/Bias/Byars/Byers work on Warren County, Tennessee, and the tangle of migrations and families, please let us know. We’d be happy to post it. There is additional information in Logan Connections on Nathan Byars, Cantrells, Delphy Logan Byars, Bethells, and more.

James Dodson Evans (Big Jim) m. Dec. 7, 1852 to Drucillah H. Byars b. Oct. 28, 1835 d. March 19, 1909, dau. of Nathan Byars b. Dec. 27, 1808 d. Jan. 12, 1894 and Nancy Hand Byars b. Mar. 12, 1812 d. Sept. 9, 1887. They had 7 children who are listed in Lynn’s book.

I didn’t find any Logans listed in Lynn’s book.

Ragland v. Ragland lawsuit, either Washington or Perry County, Illinois, 1872

This abstract from a Sparta, Randolph County, Illinois newspaper about a Ragland v. Ragland lawsuit contains helpful genealogical information. Washington County, Illinois, is mentioned but some of the Raglands lived in Perry County, Illinois (close to the Perry-Washington County boundary in both cases.) It wasn’t clear from the clipping in which county the lawsuit was filed.

Benjamin Ragland and Nancy, his wife, John Ragland and Patsy, his wife, Elijah Harris and Patsy, his wife, Allen Williams and Catherine, his wife, William Rainey and Harriett, his wife, Hawkins Ragland and Lucinda, his wife, Samuel S. Maxwell and Serilla, his wife, heirs of John Ragland, late of Washington County, deceased.

vs.

Moses Jackson, in right of his wife, Nancy, deceased [Jackson children all named], Rebecca Ragland, wife of Joseph T. Ragland, deceased, Briant West and Ruth, his wife, Elizabeth W. Ragland, John Ff. Maxwell and Emily Frances, his wife, Wm. F. Maxwell and Catherine, his wife, George W. Ragland, Zachariah B. Ragland, John L. Ragland, and Hawkins Ragland, heirs of Joseph T. Ragland, deceased.

The Logans and Raglands are connected this way: Nancy Dodson, daughter of Dillingham Dodson and Mahala Logan Dodson, married Benjamin Ragland in Allen County, Kentucky. Mahala Logan was the daughter of Joseph Logan and Anna “Annie” Bias Logan and the sister of Zachariah Logan.

Nancy Dodson Ragland and Benjamin Ragland had a son named Dillingham Ragland. He married Ruth A. Maxwell in Washington County, Illinois. Their son, Benjamin Ragland, mentioned above, was born in Washington County, IL.

Source: “Abstracts from Sparta, Illinois Newspapers,” Branching Out from St. Clair County, Illinois, Volumes 22-24, Marissa Historical and Genealogical Society, Marissa, St. Clair County, Illinois, 1994

“A Bill to Bring Traitors to Trial,” North Carolina, 1782

The Revolutionary War was a civil war, too, especially in the upcountry of North and South Carolina. In 1782, the North Carolina legislature prepared “A Bill to Bring Traitors to Trial.” Among the names of Loyalists branded as traitors is one with Logan ties, Moses Moore (“Moor” in the document), and his son, Benj. Moore (“Moor”).

Despite being one of the signers of the Tryon Resolves in Tryon County, North Carolina, in 1775, Moses Moore ultimately threw in his lot with King and country. In his mind, of course, he was a patriot.

His son, John Moore, was a Loyalist (Tory) leader at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill.

A daughter, Sarah Moore, married Drury Logan. Another daughter, Hester, married Joshua Roberts. Both Drury Logan and Joshua Roberts chose the other side in the Revolution: the Patriot (Whig) side. Much of the Drury Logan profile in Logan Connections consists of his and Joshua Roberts’ efforts (as well as Joseph Lawrence who married Moses Moore’s other daughter, Ann) to work and litigate to protect their father-in-law’s land and other assets from confiscation. This was no doubt a sometimes unpopular path to tread, but Logan and Roberts’ bona fides as Patriots made their efforts acceptable to some at least, but most importantly, acceptable in the eyes of the law.

Benj. Moore, the other “Moor” named in the bill as a traitor, was Moses Moore’s son. We don’t know much about him, but he was said to be dead by 1785.

The Moores were two of the 36 men charged with Revolutionary War treason in Rutherford County, North Carolina, alone.

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War, also ended confiscation of Loyalist land and property. At that point, the North Carolina legislature passed “An Act of Pardon and Oblivion.”

Moses Moore ended up a refugee in Spanish West Florida, a haven for Loyalists originally engineered by the British King in what was then British West Florida.

Among the other “traitors” singled out from Rutherford County, North Carolina, who have a connection, although tangential, with some of our Logans are the Bickerstaff or Biggerstaff family. The Biggerstaffs, like the four Logan brothers, William, Joseph, John, and Thomas, were a family with split loyalties who fought at the Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780. The “Bickerstaffs” named in “A Bill to Bring Traitors to Trial” in 1782 were Samuel, Aaron, and Benjamin. Aaron Biggerstaff, a Tory, fought at Kings Mountain. He was said to be mortally wounded, yet his name is on the list of “traitors.” Benjamin Biggerstaff was a Whig / Patriot, by many accounts, yet family tradition has him switching sides during the war as many did, depending on the fortunes of war and their and their families’ best interest. I believe Samuel Biggerstaff was the father — and a Tory.

In a further example of tangled loyalties, John Moore, Tory commander at Ramsour’s Mill and Moses Moore’s son, was a cousin of the Biggerstaffs.

When the Patriots left Kings Mountain after their stunning victory, Loyalist prisoners in tow, they stopped at the Biggerstaff plantation for a drumhead trial of alleged traitors captured at the battle. The selection of the Biggerstaff location was probably not coincidental. Several Loyalists were hanged there before the summary executions were stopped. It’s possible that some or all of the Logan brothers, except Thomas left wounded on the battlefield, witnessed these hangings.

Our thanks to Joe Logan and Dr. A.B. Pruitt for background sources and information.

Sources: Abstracts of Sales of Confiscated Loyalists Land and Property in North Carolina, Dr. A.B. Pruitt, 1989; “A Bill to Bring Traitors to Trial, 1782,” Grace W. Turner, The North Carolina Genealogical Society Journal, Vol. XXVIII, No. 4, Nov. 2002, pages 420-426, researched by Joe Logan.